600,000-year-old finds point to some of Britain’s earliest humans

Early humans were present in Britain between 560,000 and 620,000 years ago, according to new research involving our Department of Geography.

The dating of archaeological discoveries, made on the outskirts of Canterbury, in Kent, England, make it one of the earliest known Palaeolithic sites in northern Europe.

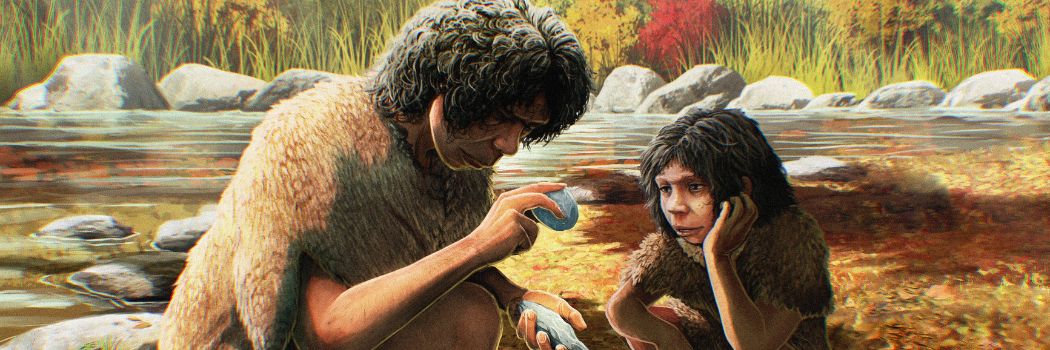

The research confirms that Homo heidelbergensis, an ancestor of Neanderthals, occupied southern Britain in this period (when it was still attached to Europe).

It also gives tantalising evidence hinting at some of the earliest animal hide processing in European prehistory.

Dating techniques

Located in an ancient riverbed, the Canterbury site was first discovered in the 1920s by local labourers who found artefacts known as handaxes.

By applying modern dating techniques to new excavations the age of the artefacts has finally been determined.

Early humans are known to have been present in Britain from as early as 840,000, and potentially 950,000 years ago, but these early visits were fleeting.

Cold glacial periods repeatedly drove populations out of northern Europe, and until now there was only limited evidence of Britain being recolonised during the warm period between 560,000 and 620,000 years before today.

Hominins were thriving

Homo heidelbergensis was a hunter gatherer known to eat diverse animal and plant foods, meaning that many of the tools found may have been used to process animal carcasses, potentially deer, horse, rhino and bison, as well as tubers and other plants.

Evidence of this can be seen in the sharp-edged flake and handaxe tools present at the site.

The presence of scraping and piercing implements, however, suggest other activities may have been undertaken, including animal hide preparation potentially for clothing or shelters.

The range of stone tools from the original finds and from new, smaller, excavations suggest that hominins living in what was to become Britain, were thriving and not just surviving.

Find out more

- The research was led by the University of Cambridge and was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

- Durham University’s part in the research was led by Professor David Bridgland in our Department of Geography. David’s involvement was linked to his expertise in river gravels, which are the source of flint artefacts, such as these handaxes, in many parts of southern Britain.

- Interested in studying Geography at Durham? See our undergraduate and postgraduate opportunities.

* Main image credit: Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Gabriel Ugueto.

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/geography/Matt_Couchmann-3872X1296.JPG)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/central-news-and-events-images/A-handaxe-artefact_Image-credit_Museum-of-Archaeology-and-Anthropology,-Cambridge.JPG)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/central-news-and-events-images/A-selection-of-flint-artefacts-excavated-at-the-site_Image-credit_Alastair-Key.png)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/central-news-and-events-images/1_Fossil-skull-cast-of-homo-heidelbergensis.-NB-NOT-FOUND-IN-THIS-EXCAVATION-_Credit-Giuseppe-Castelli-(Department-of-Archaeology,-University-of-Cambridge)-(1).jpg)

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/central-news-and-events-images/Artist-reconstruction-of-Homo-heidelbergensis-making-a-flint-handaxe_Image-credit_Department-of-Archaeology,-University-of-Cambridge_-Illustration-by-Gabriel-Ugueto.jpg)