Light-bending gravity reveals one of the biggest black holes ever found

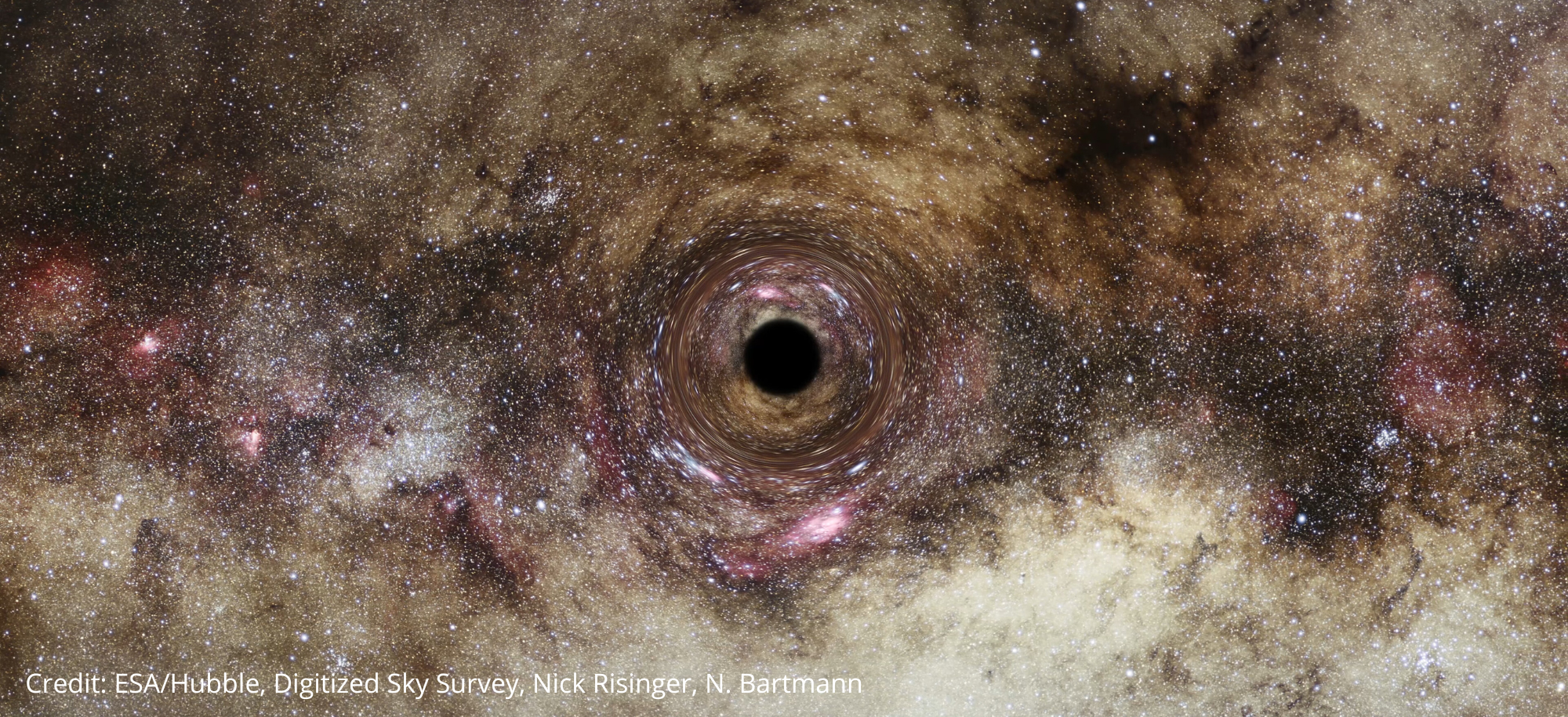

A team of astronomers, led by Dr James Nightingale from our Department of Physics, has discovered one of the biggest black holes ever found by taking advantage of a phenomenon called gravitational lensing.

Light-bending gravity

Gravitational lensing - where a foreground galaxy bends the light from a more distant object and magnifies it – and supercomputer simulations on the DiRAC HPC facility, enabled the team to closely examine how light is bent by a black hole inside a galaxy hundreds of millions of light years from Earth.

The team simulated light travelling through the Universe hundreds of thousands of times, with each simulation including a different mass black hole, changing light’s journey to Earth.

30 billion times the mass of our Sun

When the researchers included an ultramassive black hole in one of their simulations, the path taken by the light from the faraway galaxy to reach Earth matched the path seen in real images captured by the Hubble Space Telescope.

What the team had found was an ultramassive black hole, an object over 30 billion times the mass of our Sun, in the foreground galaxy – a scale rarely seen by astronomers.

This is the first black hole found using gravitational lensing and the findings have been published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Looking back in cosmic time

Most of the biggest black holes that we know about are in an active state, where matter pulled in close to the black hole heats up and releases energy in the form of light, X-rays, and other radiation.

Gravitational lensing makes it possible to study inactive black holes, something not currently possible in distant galaxies. This approach could let astronomers discover far more inactive and ultramassive black holes than previously thought and investigate how they grew so large.

The story of this particular discovery started back in 2004 when fellow Durham University astronomer, Professor Alastair Edge, noticed a giant arc of a gravitational lens when reviewing images of a galaxy survey.

Fast forward 19 years and with the help of some extremely high-resolution images from NASA’s Hubble telescope and the DiRAC COSMA8 supercomputer facilities at Durham University, Dr Nightingale and his team were able to revisit this and explore it further.

Exploring the mysteries of black holes

The team hopes that this is the first step in enabling a deeper exploration of the mysteries of black holes, and that future large-scale telescopes will help astronomers study even more distant black holes to learn more about their size and scale.

Find out more:

- Read the full paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

- Read our profile on lead author, Dr James Nightingale and visit his website.

- Watch a video about this discovery

- Checkout the software used to perform this analysis – PyAutoLens.

- Interested in studying at Durham? Explore our undergraduate and postgraduate courses.

Acknowledgements:

The research was supported by the UK Space Agency, the Royal Society, the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), and the European Research Council.

This work used both the DiRAC Data Intensive Service (CSD3) and the DiRAC Memory Intensive Service (COSMA8), hosted by University of Cambridge and Durham University on behalf of the DiRAC High-Performance Computing facility.

Physics at Durham University

Our Department of Physics is a thriving centre for research and education. Ranked 4th in the UK by The Guardian University Guide 2022, we are proud to deliver a teaching and learning experience for students which closely aligns with the research-intensive values and practices of the University.

Feeling inspired? Visit our Physics webpages to learn more about our postgraduate and undergraduate programmes.

/prod01/prodbucket01/media/durham-university/departments-/physics/teaching-labs/VT2A9034-1998X733.jpeg)